The Informal Sector: Africa’s Invisible Economic Engine

By Divine Adongo | Voices of Africa

In the heart of Nairobi’s Gikomba market, Amina spreads out secondhand clothes before sunrise. Her fingers are swift, her voice persuasive, and her business instincts razor-sharp. She has no formal training, no business degree, and no receipt machine — yet she feeds her family, pays rent, and supports her younger sister through school. Like millions across the continent, Amina doesn’t work a “formal job,” but she works every single day. And in truth, she’s not just making ends meet — she’s powering Africa’s economy.

From Accra to Abidjan, from Kampala to Kigali, the informal sector is where Africa lives, works, and survives. It’s the roadside coconut seller, the motorcycle rider, the market queen, the home-based seamstress, the mobile money agent, and the food vendor by the junction. It’s messy, unpredictable, unregulated — and essential. According to the African Development Bank, over 80% of jobs in Africa are in the informal sector, yet public policy continues to treat it like an afterthought, if not a nuisance.

Why does this matter? Because the informal sector is not just a safety net — it is the main stage. It absorbs young people when formal jobs are scarce. It sustains entire communities where state services are absent. It produces goods, delivers services, fuels transport, and even drives innovation. In countries where formal economies are sluggish, the informal sector becomes the beating heart of resilience.

Yet this sector remains invisible in policy and vulnerable in practice. Informal workers face daily threats — eviction, harassment, poor infrastructure, and lack of legal protection. They are taxed without representation, regulated without consultation, and rarely invited to economic planning tables. Governments chase them off pavements in the morning, then turn to them for votes in the evening. But the truth is simple: you cannot develop Africa by ignoring the people who are already building it.

The informal economy is not a problem to be solved — it is a reality to be respected, resourced, and reimagined. That begins by understanding its diversity. Some are survivalists — selling sachet water or plantain chips to get by. Others are dynamic entrepreneurs — running microenterprises with local employees and supply chains. Both groups deserve recognition, support, and protection. Formalization, when it comes, must not mean bureaucracy and punishment. It must mean dignity, inclusion, and opportunity.

Take Rwanda’s efforts to organize motorbike riders into cooperatives. Or Ghana’s MASLOC microfinance schemes for market women. Or Kenya’s Huduma Centres that bring services closer to the people. These models are far from perfect, but they show what’s possible when policy meets people where they are — not where the textbook says they should be.

Technology also presents a massive opportunity. Mobile payments, digital ID systems, and online platforms are allowing informal workers to scale their services, access credit, and enter larger value chains. With the right infrastructure, training, and protections, informal businesses can move from surviving to thriving.

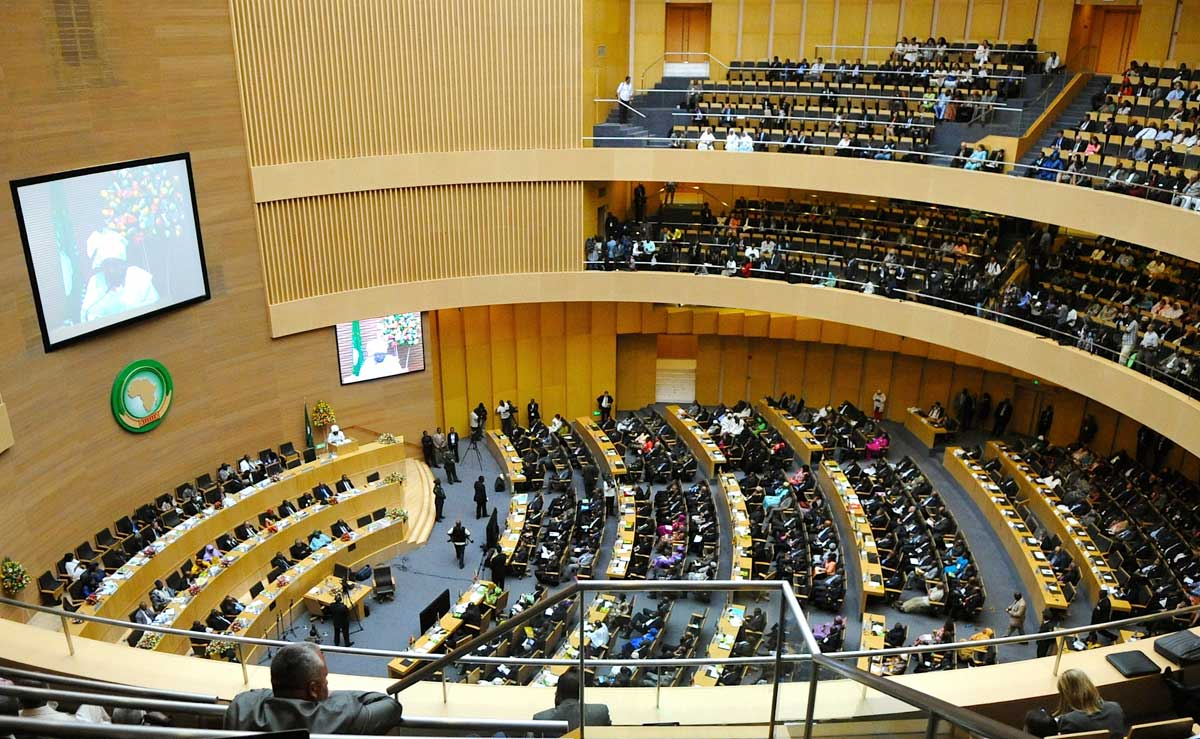

This is where the AfCFTA Academy comes in — building the capacity of Africa’s informal sector to tap into continental trade opportunities, navigate cross-border procedures, and scale their enterprises beyond local boundaries. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) isn’t just about big corporations and customs unions — it’s about people like Amina. Through training, policy education, and community engagement, the AfCFTA Academy equips Africa’s informal entrepreneurs with the tools to participate in the single largest free trade market in the world.

Because if Africa is to integrate economically, it must begin by empowering those who already trade across borders — often informally, and often without support. From women-led markets in West Africa to mobile artisans in East Africa, the real energy of trade lies in the hands of the people. The AfCFTA must rise with them — or risk leaving them behind.

But beyond programs and platforms, what’s needed most is respect. A new narrative. The informal sector should not be portrayed as backward or illegal but as enterprising, adaptive, and central to Africa’s future. Policymakers must listen to their voices, understand their needs, and co-create solutions. Urban planning must include space for hawkers and traders. Financial institutions must create products for informal savers and borrowers. Education systems must prepare youth not just to seek jobs — but to build livelihoods, even outside the formal grid.

For Pan-Africanists, this is about economic justice. It is about ensuring that the millions who keep our cities fed, clothed, and moving are not excluded from national visions of progress. It is about recognizing that Africa’s economic transformation will not come solely from boardrooms and foreign investment — but from kiosks, wheelbarrows, sewing machines, and open-air stalls.

Amina, the vendor in Gikomba, may never appear in GDP figures or wear a suit to work. But she is a businesswoman. A taxpayer. A citizen. A natural entrepreneur. And through platforms like the AfCFTA Academy, she can become a continental player, not just a local survivor.

She deserves to be seen. She deserves to be supported. She deserves to trade freely.