African Indigenous Approaches to Conflict Resolution

By Divine Adongo | Voices of Africa

Long before colonial borders carved the continent into fragments, before peacekeeping missions wore blue helmets and before legal systems spoke in foreign tongues, Africa had its ways of making peace. Under the baobab tree, in the chief’s compound, or during the long fireside nights, communities resolved disputes not through judges and jails, but through dialogue, restitution, and restoration. The elders listened, the offender confessed, and the goal was not punishment, but healing.

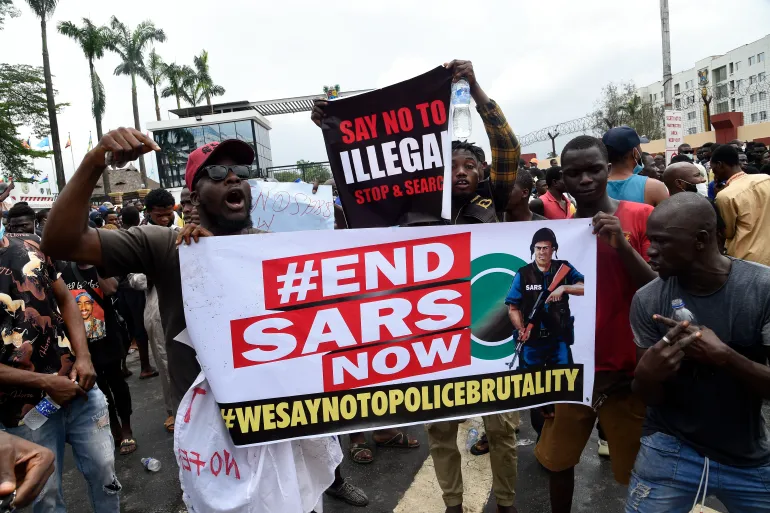

Today, in a world shaped by Western legal traditions and formal institutions, Africa’s indigenous approaches to conflict resolution are often dismissed as outdated or informal. Yet, for millions across the continent — especially in rural and post-conflict communities — these traditional systems remain the first and most trusted line of defense against violence and division. When government courts are corrupt or inaccessible, and when national peace efforts feel distant, the community becomes the court, and wisdom becomes law.

In Ghana, the chieftaincy institution continues to mediate land disputes that formal courts have failed to resolve. In Rwanda, Gacaca courts brought communities together after the 1994 genocide to pursue truth, forgiveness, and reconciliation — a process imperfect, yet deeply rooted in Rwandan traditions. In Somalia, the Xeer system — a customary law upheld by elders — has managed clan conflicts in places where the central state has collapsed. In Zimbabwe, Dare councils still meet to settle family disputes, and in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, interfaith dialogue among local leaders has prevented entire communities from descending into war.

These examples reveal a profound truth: peace in Africa is not imported — it is inherited. Our ancestors knew that the goal of justice was not to destroy the wrongdoer, but to restore balance. They knew that no peace could last unless the community was whole. Their wisdom, passed down through proverbs, rituals, and practices, is not archaic — it is urgent.

Yet, despite their effectiveness, indigenous peace systems face marginalisation. Colonialism undermined their authority by replacing them with foreign laws. Modern governance often sidelines them in favour of bureaucratic systems ill-equipped to handle grassroots tensions. Some traditional mechanisms have also been corrupted by politics or weakened by generational disconnects. And yes, not all traditional systems are perfect — some have perpetuated gender discrimination or reinforced social hierarchies. But rather than reject them entirely, we must reform and reintegrate them into national peace frameworks.

The future of peace in Africa lies in blending the old and the new. Imagine a justice system where traditional councils work alongside modern courts, where elders and judges collaborate to resolve conflict, where cultural mediators are formally trained and resourced. Imagine peace education that includes African proverbs, storytelling, and ancestral wisdom, not just theories from textbooks written elsewhere.

For Pan-Africanists, reclaiming indigenous peacebuilding is an act of decolonisation. It is a refusal to believe that African solutions are inferior. It is a reminder that while conflict is often imported through arms, ideologies, and exploitative interests, peace can be homegrown. In a continent with over 3,000 ethnic groups, diverse faiths, and complex histories, no one-size-fits-all peace model will work. But every community has within it the seeds of reconciliation — we just need to water them.

To support indigenous peacebuilding, African governments must officially recognise and fund traditional authorities as partners in security. Development actors must invest in training and documentation of traditional systems. Youth must be taught the value of these practices, and elders must be empowered to adapt them to today’s challenges. Most importantly, we must shift our mindset to see our heritage not as backward, but as brilliant.

The baobab tree still stands. Beneath it, the tools for peace are waiting: listening, accountability, truth-telling, forgiveness, and healing. If Africa is to silence the guns, it must also amplify the voices of its elders, the wisdom of its cultures, and the power of its people to resolve their own conflicts — not through force, but through understanding.