Civic Participation and the Power of the People

By Divine Adongo | Voices of Africa

Why Democracy Must Be Lived, Not Just Voted.

In a rural town in Uganda, a woman named Grace wakes up at dawn, not to fetch water or cook for her children — but to walk five kilometers to her district assembly hall. She is not a politician, nor is she a delegate. But today, she will speak. Today, her voice — like many others across the continent — has become a small yet powerful thread in the fabric of Africa’s fragile democracy.

Democracy in Africa has often been reduced to election day — that single moment every four or five years when citizens queue under the sun, ink-stain their thumbs, and cast their hopes into ballot boxes. But what happens after the votes are counted? For many, the answer is silence. No town hall meetings. No budget consultations. No responses to petitions. Just long years of governance done to them, not with them. But democracy, as Africans are increasingly declaring, is not an event — it is a way of life.

True civic participation means citizens are involved — daily, actively, and meaningfully — in the decisions that shape their lives. It means that young people help write policies, not just protest them. It means that women lead in budgeting meetings, not just vote for men who ignore them. It means that communities shape development priorities, monitor projects, question leaders, and co-create the future.

Across the continent, the desire for real democracy — one that includes people’s voices beyond the polls — is rising. From the youth councils in Senegal to participatory budgeting in Kenya, from citizen report cards in Ghana to social audits in South Africa, Africans are showing that civic engagement is not a Western import — it is a Pan-African imperative. Long before colonial rule, African societies practiced participatory governance through village assemblies, councils of elders, and communal decision-making. The people governed through dialogue, not decrees.

Yet today, civic participation remains under threat. In many countries, civic space is shrinking. Protestors are arrested. NGOs are labeled as foreign agents. Journalists disappear. Whistleblowers face retaliation. And those who dare to question authority are branded as enemies of the state. But suppression cannot sustain stability. A government that fears its people cannot govern them. Silencing voices does not strengthen democracy — it strangles it.

There is also the quieter threat of apathy. Decades of broken promises and recycled leadership have left many feeling that participation doesn’t matter. “Why vote?” some ask, “They will choose who they want anyway.” This disillusionment, while understandable, is dangerous. Because when good people retreat from public life, bad actors take control. When citizens disengage, corruption thrives. And when the people stop speaking, power speaks for them.

That’s why civic education is critical. Africans must know not just their rights, but also their roles. Participation is not only about protest; it’s also about proposing solutions. It’s about attending local meetings, monitoring budgets, filing requests, and staying informed. Technology is making this easier. From mobile apps that track spending to online petitions and e-parliament platforms, digital tools are giving citizens new ways to engage. But technology alone cannot substitute for trust. For civic participation to thrive, governments must create genuine, safe spaces for dialogue and dissent.

To the youth of Africa, the message is clear: you are not too young to lead — and certainly not too young to engage. Join school boards. Organize debates. Volunteer. Ask hard questions. Run for local office. Build platforms, movements, and cooperatives. You are not the leaders of tomorrow — you are the conscience of today.

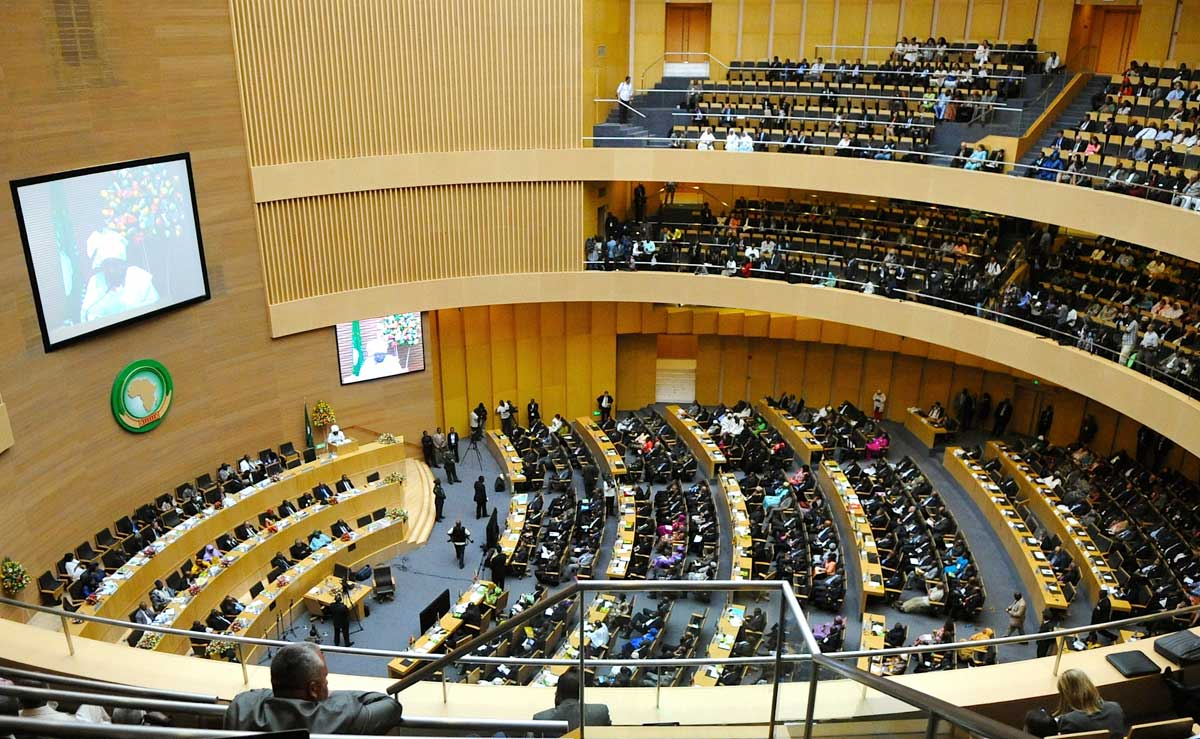

For Pan-Africanists, the mission is even broader: to create a continent where participation is not a privilege, but a practice. A continent where no one is too poor to be heard, too rural to be seen, or too young to count. A continent where democracy is not delivered from above but demanded and lived from below.

Because in the end, democracy is not just about institutions — it is about people. And the more the people participate, the more powerful their democracy becomes.