From Protests to Policies

By Divine Adongo | Voices of Africa

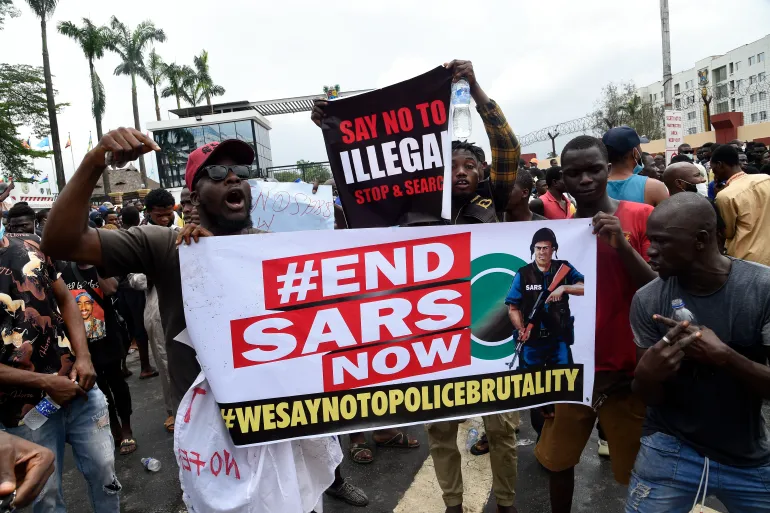

In the heart of Lagos, a sea of youth waved flags and raised their voices in unison: #EndSARS! The streets pulsed with energy, defiance, and hope. For days, they occupied the public space, demanding an end to police brutality. But beyond the chants and placards, there was something deeper stirring — a generation daring to believe that protest could give birth to policy.

Across the African continent, protests have become the loudest language of the unheard. In Sudan, young people helped topple a three-decade dictatorship. In Senegal, youth-led resistance delayed constitutional manipulation. In Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tunisia, and Eswatini, crowds have gathered again and again to say, enough is enough. But too often, the story ends there — with police crackdowns, temporary reforms, or co-opted demands. The question remains: how do we turn protest into policy? Outrage into institutional change?

The answer is not easy — but it is essential. Protests are necessary. They disrupt complacency. They awaken societies. They shift public discourse. But protests alone are not sufficient. What comes after the protest determines whether the energy becomes a movement or just a memory. And for that transformation to happen, African citizens must move from the streets to the strategy rooms, from placards to policy papers, from hashtags to handshakes — without losing their fire.

The first step is organization. Spontaneous protests capture attention, but organized movements shape outcomes. After the marches end, there must be teams drafting reform proposals, engaging lawmakers, holding town halls, and negotiating for real change. Policy change does not happen by protest alone — it happens by persistence, planning, and pressure over time.

Second is translation — turning street demands into actionable language. For example, saying “end police brutality” must evolve into demands like independent police oversight commissions, legal reforms, budget reallocation, and community policing models. When demands are clear and measurable, they are harder to ignore — and easier to monitor.

Third is representation. Movements need trusted spokespersons — diverse, grounded, and accountable — who can engage power without being swallowed by it. These individuals must enter boardrooms, parliamentary hearings, and media spaces, not as elites detached from the people, but as extensions of the people’s voices. Leadership in movements must be principled, not performative.

Fourth is institutional engagement. This doesn’t mean abandoning protest — it means complementing it with civic pressure on institutions: tracking votes in parliament, proposing citizen bills, leveraging legal systems, attending public budget meetings, and forming watchdog groups. When citizens participate in the slow, frustrating work of democracy, they slowly reshape the institutions from within.

But perhaps most importantly, citizens must resist the temptation to outsource change to politicians alone. True democracy is not just about changing leaders — it’s about changing how leadership works. A new president is not a new system. Real change requires citizens who do not sleep after elections, who do not go silent after protests, who follow the money, demand justice, and show up even when cameras aren’t watching.

There are signs of hope. In Tunisia, youth activists influenced constitutional reforms after the Arab Spring. In Ghana, the #FixTheCountry sparked national conversations on public accountability. In Kenya, grassroots pressure led to the enactment of the Access to Information Act. These wins were not immediate — they came from strategic, sustained civic action. And they remind us that when citizens stay engaged beyond the moment of protest, policies follow.

For Pan-Africanists, this is a call to reimagine activism not as an emotional reaction, but as a disciplined mission. To build civic literacy, legal knowledge, and organizational capacity across the continent. To teach our youth not only to march — but to mobilize, legislate, and lead.

Protest gives us the power to say no. Policy gives us the power to say yes — to a new system, a fairer law, a better budget. Africa needs both: the fire of protest and the framework of policy. One disrupts; the other rebuilds. Together, they make governance accountable.

Because true freedom is not just the right to shout — it is the power to shape.