Good governance: A prerequisite for peace?

By Padiwanashe Mataranyika | Voices of Africa

“A child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.”

With just one sentence, this Igbo proverb captures the essence of governance — that when people are neglected and mistreated, they often rebel. In 2021, UNDP author Yoshihiro Saito posed a powerful question: ‘Is good governance truly a necessary precursor to peace?’. At a glance, the answer may seem obvious, yet it’s a question that demands more than a rehearsed response. An important topic, without a doubt. But this subject often feels overextended, even exhausted, in policy discourse. Perhaps the real question we should be asking is: Can peace and security exist where bad governance persists? And if it does, is it genuine and lasting, or merely the uneasy calm of a population that has been silenced — is it nothing but the hollow quiet of a fragile state teetering on volatility?

I recently argued that good governance in Africa is a myth — a fairytale promising milk and honey to the hopeful but weary African. But for the righteous leaders, those who still carry just enough fear of God in them, good governance is not a vague aspiration; it is a concrete framework for how power should be exercised, decisions made, and resources distributed. At its core, it is about fairness, transparency and accountability. It means building systems where leaders serve the people, not themselves, where laws are applied equally, and where citizens feel seen, heard, and protected. Good governance should not be a luxury, a daydream by street kids on a sun-scorched day. Good governance is the foundation of every just society. And where it is absent, peace becomes difficult to sustain.

But let’s revisit the original question. ‘Is it possible to have peace where there is bad governance?’ Is good governance the only prerequisite for peace? Does bad governance always translate to unrest and instability? The answer isn’t as clean-cut as a six-page chapter in a Peace and Security textbook, with a quiz at the end. Governance is complicated and not a one-size-fits-all; it is not straightforward or formulaic. First, we must ask, what exactly is peace? The dictionary definition describes peace as a state of tranquility and an absence of conflict and violence. By this definition alone, it becomes clear that even badly governed nations can have “peace”.

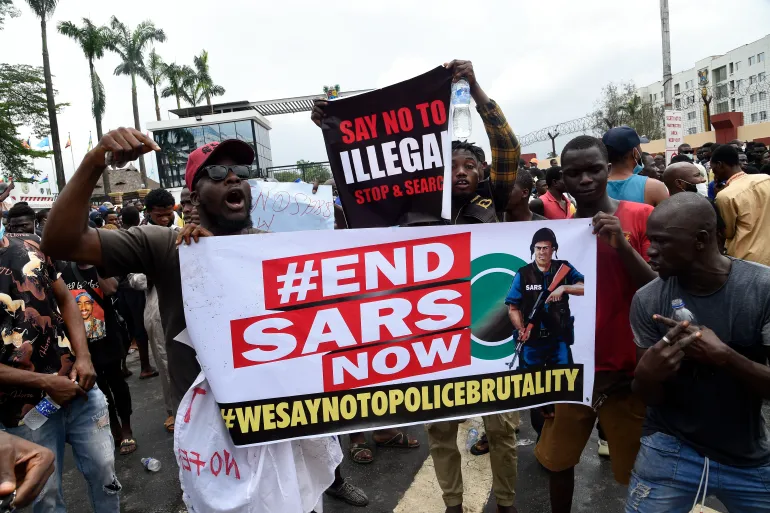

However, It is possible for a country to appear peaceful while quietly unraveling beneath the surface. Even in places where armed conflict is absent, bad governance breeds quiet instability. Examples of this dynamic are everywhere. The Arab Spring was not sparked by ideology; it was a response to decades of repression, inequality, and economic exclusion. Yes, peace can exist under bad governance, but this peace is often shallow, fragile, and rooted in fear and oppression. It is performative and often one injustice away from collapse. Peace, under these conditions, is not peace at all; it is the hush before the eruption. The calm before the storm.

Good governance doesn’t just aim to avoid war. Good governance, by contrast, seeks to prevent conflict by building systems of trust, justice, and accountability. Good governance ensures that calm is not a product of silence, but of satisfaction — that people are not merely avoiding violence, but living in dignity. Peace is not the absence of war and bullets. That standard and definition are the crutch of lazy thinking. Peace is the deep exhale of a people who no longer have to hold their breath. True peace is not achieved by silencing the oppressed, but it is the stillness of a people who know that they are safe, heard, and valued.

Because in the end, peace that is built on intimidation and injustice is not peace at all. It is a postponement of the inevitable.

It is delay.

Author

Padiwanashe Mataranyika is the Southern Africa Regional Ambassador for CCPA. She holds a degree in Law and a Master’s in International Relations, Diplomacy, and Management. Padiwanashe is the founder of The Moyo Muti Initiative, a grassroots project providing relief and support to rural schoolchildren. She is an AMEL Project Fellow, recognised for her passion for peacebuilding and her advocacy for human rights in conflict-affected regions. Passionate about African solutions to African challenges, her work explores how good governance can transform communities from the ground up.

“Because in the end, peace that is built on intimidation and injustice is not peace at all. It is delay.”

I wonder how many African governments realize that they are living blissfully ignorant of the ticking time bombs in their houses? One would think, looking at the Libyan Muammar Gaddafi, or the Zimbabwean Robert Mugabe that nothing is permanent and that a hive that is continuously agitated by other forces will erupt in anger.

This is a great read from this writer. Thank you.

This is a well written article that reflects what is obtaining in most of our countries on the African continent. Yes, this article resonates correctly with Johan Galtung’s definition of peace, which includes “negative peace”- the absence of violence or war, and “positive peace” – presence of social justice, harmony, structural and cultural transformation.